Don Quixote is a novel that has truly earned all the praise it has received, one that has withstood the test of time, and one that still carries meaning today because it is universal and timeless. Perhaps the greatest novel ever written. The first and still the best. If I were to choose a single novel as the greatest, I would likely choose Don Quixote, though I might waver slightly between it, War and Peace, and Moby Dick. Not to mention drama and tragedy, where I would naturally include Shakespeare and the Greek Tragedians.

This novel was published in two volumes. Many renowned scholars and critics worldwide, including Goethe, preferred the first volume of the novel, while others hold the second in higher regard. I, too, prefer the second volume, which I consider superior to the first.

"Don Quixote of La Mancha has always been, for every era and every place, one of the most popular works in the world, popular among both the common folk and the gloomy philosophers like Kant and Schopenhauer. Edward Fitzgerald called it the most delightful work in the world," writes Noli.

Noli did a wonderful job with the Albanian adaptation (adaptation, not translation) of Cervantes' novel, but the interpretation he offers in the preface is not without fault. He could not resist using the characters of his adaptations as tools for political propaganda of the time. Thanks to Noli, the words "Don Quixote" and "quixotic" have entered the Albanian lexicon and are known by everyone, even those who have never read Cervantes' novel. However... these words have been unjustly imbued with a pejorative meaning by our wise Noli, who called Don Quixote the epitome of Albanian beyliks:

"Cervantes chose as the heroes of his work two of the most reactionary and medieval types: the bey, the backward and fanatical village lord, Don Quixote of La Mancha, and the rogue, the ignorant and poor peasant, Sancho Panza. These two take upon themselves the burden of reviving the era of the errant knights, that is, to turn Spain and the entire world backward; from capitalism to feudalism; from cannons and guns to spears and clubs; from science to magic; from history to myths; from progress to darkness,"

writes Noli in his famous preface. He continues:

"Don Quixote seeks and finds work as an errant knight, as his ancestors were. Don Quixote seeks and finds his foundation in the tales of his class, in the books of chivalry.What does it matter that the world has moved forward? Don Quixote takes it upon himself to turn the world backward, as the interest of his class demands. As a natural companion in this crusade, Don Quixote finds the poor and ignorant peasant, Sancho Panza, who is at his doorstep. For he, too, has been left without work or economic help and finds himself in a similar state to Don Quixote."

It is necessary to revisit this interpretation, which has now become entrenched in our culture. An interpretation found in every educational analysis. Our mad but noble knight deserves his honor restored. This interpretation is deeply flawed and does not do justice to Cervantes' monumental and complex work. Noli, with all due respect... here you have strayed far from the truth, driven by political passion, or a passion for paradox and opposition, or for the sake of fiction and metaphor. A passion that often captures even the brightest minds! A passion that led even a giant like Tolstoy to dismiss Shakespeare as an artificial, insignificant writer, and Hamlet as a story of ghosts... Noli could not be spared. Even Kadare has rightly criticized him for this.

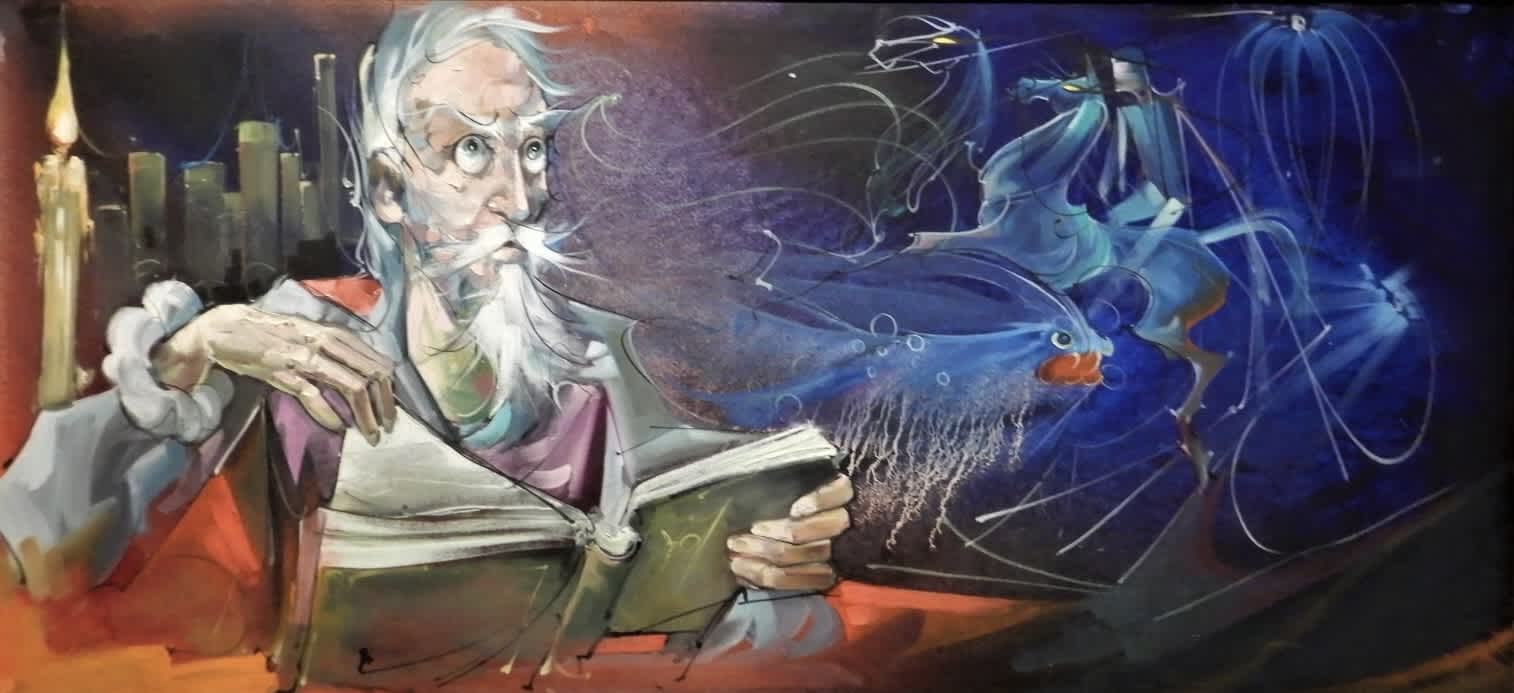

Don Quixote is the personification of pure and utopian idealism, a naive desire for good and justice to triumph in the end. A daydreamer, yes, but one with noble dignity who does not surrender to a distorted reality. In Sancho Panza, we find the wisdom and sharpness of the common folk, practical and grounded.

Today, Don Quixote is known as a comical character, one who makes us laugh and mock. With this connotation, we mock someone by labeling them "quixotic."

Nabokov said:

"We no longer laugh at Don Quixote. His deeds are to be pitied, his creed is beauty. He is a symbol of nobility, perseverance, purity, kindness, and altruism."

While Lord Byron expressed:

"Of all tales 'tis the saddest - and more sad, Because it makes us smile."

Nabokov is right when he says that his creed is beauty. His madness has a poetic foundation. It is an appeal to this overly superficial world, which has lost the ability to dream and be inspired, an appeal to a reality deprived of beauty. His madness is also that of a philosopher with grand and profound thoughts. Not for nothing, on page 140 of the second volume, Cervantes describes him (through the words of the hosts where Don Quixote was a guest):

"Our guest cannot be swayed from the grip of his madness by all the doctors and medicines in the world: for his insanity speaks the language of reason, and the dark well into which his thoughts have plunged has cracks of light."

Personally, I have never liked the association of the comical, the hallucinatory, and the delusional with Don Quixote, who, along with Sancho Panza - whom Noli called a rogue and an ignorant peasant - wanted to turn back the wheel of history. Don Quixote does not seek to turn back the wheel of history; he is a humanist.

In the first book, Chapter 11, What Happened to Don Quixote with Some goatherds, page 68, he says:

“What a happy time and a happy age were those that the ancients called Golden! And not because gold - which in this our Age of Iron is so valued - was gotten in that fortunate time without any trouble, but rather because the people who lived then didn’t know the two words yours and mine! In that holy age all things were commonly owned. To find their daily sustenance, they had only to raise their hands and take it from the robust oaks, which liberally offered their sweet and ripe fruit to them. the fertile harvest of their very sweet work. Everything then was friendship, everything was harmony. [...] In those days, literary expressions of love were recited in a simple way, without any unnatural circumlocution to express them.

“Fraud, deceit, and wickedness had not as yet contaminated truth and sincerity. Justice was administered on its own terms and was not tainted by favor and self-interest, which now impair, overturn, and persecute it. Arbitrary law had not yet debased the rulings of the judge, because in those days there was nothing to judge, nor anyone to be judged.

“Young women, with their chastity intact, traveled about on their own anywhere they wanted, as I’ve said, without fearing the damaging boldness or lust of others, and if they suffered any ruination it was born of their own pleasure and free will. Nowadays, in our detestable age, no young woman is secure, even though she be hidden and locked in a new labyrinth of Crete.

As time went by and as wickedness grew, the order of knight errantry was instituted to defend young women, protect widows, and help orphans and needy people. “I am a member of this order, brother goatherds."

The belief in these virtues of humanity's origins, in its ancient connection with nature, was also echoed by the philosophers of the European Renaissance and later by those of the modern era, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau. To return to this golden age, our knight mounted his horse and set out on his journey, seemingly pathetic and mad, but noble. His sword serves those in need. A sword that sought to cleanse the world's injustices and save virtue, which "is pursued by the wicked more than it is loved by the good," but "virtue is so strong that it will triumph in every battle and shine throughout the world, like the sun in the sky," as expressed by the Knight of the Sorrowful Face in the first book, pages 319-320.

Such enthusiasm as Don Quixote's is not found in any other hero of the Enlightenment era. "Noble madness" is what Don Diego calls it in the second book. Even in the prologue of the second book, Cervantes himself calls it "wise madness."

Don Quixote was, therefore, a perpetual warrior, who, as always, had to be, in his own words, "honest in speech, generous in deeds, brave in actions, compassionate to the poor, and, finally, an unwavering champion of truth, even if it cost him his life," from the second book, page 140.

For Don Quixote, noble virtue is earned, and thus it has authentic value, unlike the noble blood of princes, which is inherited and therefore lacks that value. As we see, our knight is not at all the epitome of Albanian beyliks. Don Quixote may be an incorrigible dreamer, but he is a knight of freedom.

“Freedom, Sancho, is one of the most precious gifts heaven gave to men; the treasures under the earth and beneath the sea cannot compare to it; for freedom, as well as for honor, one can and should risk one’s life, while captivity, on the other hand, is the greatest evil that can befall men. I say this, Sancho, because you have clearly seen the luxury and abundance we have enjoyed in this castle that we are leaving, but in the midst of those flavorful banquets and those drinks as cool as snow, it seemed as if I were suffering the pangs of hunger because I could not enjoy them with the freedom I would have had if they had been mine; the obligations to repay the benefits and kindnesses we have received are bonds that hobble a free spirit. Fortunate is the man to whom heaven has given a piece of bread with no obligation to thank anyone but heaven itself!”

It is true that Don Quixote has such a noble soul, such a great heart, and such a far-reaching vision. He is a warrior of truth and justice, but on the other hand, Cervantes does not hesitate to place our hero in the most absurd and comical situations, where the hero is not spared mockery, scorn, or even beatings. Why does Cervantes constantly parody him while simultaneously giving him all these admirable traits? Because the entire novel is a parody of romances and knights who seek to change the world, or to turn it backward, as Noli claimed? Or because Cervantes, in this way, seeks to show that heroes with truly pure souls like Don Quixote's are powerless to change a wicked world dominated by vice, egoism, and evil? Or perhaps to show that without this kind of dreaming, without the help of imagination and naivety, there can be no inspiration, no beauty?

To mention Noli and his interpretation once more, it seemed as though he had read and studied extensively the criticism of Don Quixote and had synthesized an interpretation that has now become the standard. In one article, Noli wrote:

"Thousands of critiques have been written about Don Quixote. Most of these are flawed, though their critiques seem beautiful and profound. Some, like the Russian writer Turgenev, present Don Quixote as a tragic hero in line with Hamlet. Others, like the French writer Anatole France, present him as a comic buffoon, with whom the common folk laugh. The truth lies elsewhere. Don Quixote is tragic subjectively, that is, for himself, and comic-objectively, that is, for the outsider. Can he then be called tragicomic? Perhaps, but even this does not quite fit, for Don Quixote is a category of his own. Anyway, this is not of great importance for understanding Don Quixote well. The main significance lies in Don Quixote's class, the class of beyliks. Most critics do not even mention this, though it is the root of Don Quixote's character."

Turgenev's explanation, which Noli ironically dismisses as flawed and takes a highly critical stance (this because Turgenev's perspective does not align with Noli's aim to adapt it to the context of Albanian reality), is, in my opinion, the most beautiful explanation of Don Quixote, and with it, I could conclude this review.

Turgenev wrote in his essay "Don Quixote and Hamlet":

"What does Don Quixote represent? First and foremost, faith; faith in something eternal, unshakable, in truth, in a word, in the truth that exists outside the individual man. Don Quixote is filled with devotion to the ideal, for which he is ready to endure all kinds of privations, to sacrifice his life; he values his own life only insofar as it can serve as a means for the realization of the ideal, for the triumph of truth and justice among men. We are told that this ideal was created by his sick imagination during his readings of chivalric romances; we accept this - and here lies the comic aspect of Don Quixote; but the ideal itself remains untouched in all its purity."

Don Quixote touches on many themes, each deserving of its own essay. In Chapters 12-14 of the first book, Cervantes introduces us, through the tale of Marcela and Chrysostom, to the theme of unconventional defense of women's rights. One could even say that this tale could be given a feminist rereading.

Marcela, a wealthy orphan, had chosen not to marry and had become a shepherdess, living happily in the woods. Chrysostom, out of love for Marcela, dressed as a shepherd to follow her. Upon realizing that Marcela was simply not interested in him, he took his own life. The theme then centers on the conventional judgment of the disdainful lady who caused the shepherd's suffering and death. Marcela's theme has been interpreted in various ways over time. Her figure has been personified at times as the Madonna, at times as 'la pastora superhumana'. Her discourse has been seen as 'el discurso de una libertad femenina'. Many critics find it unbelievable that Marcela could be happy without the company of men. Some even said that Marcela's figure could not be credible. And not a few seemed outraged by Marcela's indifference to Chrysostom's death, saying that her famous discourse was inappropriate and arrogant, that respect for the man who took his own life for her should have at least made her silent.

Cervantes marginalizes Marcela and makes her renounce all the good things and advantages given to her, which Simone de Beauvoir would call "the traditional alliance of women with the superior caste" (Beauvoir sees the material situation of woman's dependence and submission as essential to her explanation of female complicity. However, Beauvoir also suggests that there may be certain benefits to being "complicit." Refusing complicity with men would mean renouncing all the advantages that the alliance with the superior caste gives them [women]. The man-master will materially protect the woman and will be responsible for justifying her existence: besides the economic risk, she avoids the metaphysical risk of a freedom that must invent its own purposes without help.

— Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex).

But it was precisely Marcela's marginality that would become her greatest strength. I bring here Marcela's beautiful and clever discourse before her accusers at Chrysostom's burial:

“Heaven made me, as all of you say, so beautiful that you cannot resist my beauty and are compelled to love me, and because of the love you show me, you claim that I am obliged to love you in return. I know, with the natural understanding that God has given me, that everything beautiful is lovable, but I cannot grasp why, simply because it is loved, the thing loved for its beauty is obliged to love the one who loves it. Further, the lover of the beautiful thing might be ugly, and since ugliness is worthy of being avoided, it is absurd for anyone to say: ‘I love you because you are beautiful; you must love me even though I am ugly.’ But in the event the two are equally beautiful, it does not mean that their desires are necessarily equal, for not all beauties fall in love; some are a pleasure to the eye but do not surrender their will, because if all beauties loved and surrendered, there would be a whirl of confused and misled wills not knowing where they should stop, for since beautiful subjects are infinite, desires would have to be infinite, too.”

“According to what I have heard, true love is not divided and must be voluntary, not forced. If this is true, as I believe it is, why do you want to force me to surrender my will, obliged to do so simply because you say you love me?” “But if this is not true, then tell me: if the heaven that made me beautiful had made me ugly instead, would it be fair for me to complain that none of you loved me? Moreover, you must consider that I did not choose the beauty I have, and, such as it is, heaven gave it to me freely, without my requesting or choosing it. And just as the viper does not deserve to be blamed for its venom, although it kills, since it was given the venom by nature, I do not deserve to be reproved for being beautiful, for beauty in the chaste woman is like a distant fire or sharp-edged sword: they do not burn or cut the person who does not approach them. Honor and virtue are adornments of the soul, without which the body is not truly beautiful, even if it seems to be so. And if chastity is one of the virtues that most adorn and beautify both body and soul, why should a woman, loved for being beautiful, lose that virtue in order to satisfy the desire of a man who, for the sake of his pleasure, attempts with all his might and main to have her lose it?

I was born free, and in order to live free I chose the solitude of the countryside. The trees of these mountains are my companions, the clear waters of these streams my mirrors; I communicate my thoughts and my beauty to the trees and to the waters. I am a distant fire and a far-off sword. Those whose eyes forced them to fall in love with me, I have discouraged with my words. If desires feed on hopes, and since I have given no hope to Grisóstomo or to any other man regarding those desires, it is correct to say that his obstinacy, not my cruelty, is what killed him. And if you claim that his thoughts were virtuous, and for this reason I was obliged to respond to them, I say that when he revealed to me the virtue of his desire, on the very spot where his grave is now being dug, I told him that mine was to live perpetually alone and have only the earth enjoy the fruit of my seclusion and the spoils of my beauty; and if he, despite that discouragement, wished to persist against all hope and sail into the wind, why be surprised if he drowned in the middle of the gulf of his folly? If I had kept him by me, I would have been false; if I had gratified him, I would have gone against my own best intentions and purposes. He persisted though I discouraged him, he despaired though I did not despise him: tell me now if it is reasonable to blame me for his grief! Let the one I deceived complain, let the man despair to whom I did not grant a hope I had promised, or speak if I called to him, or boast if I accepted him; but no man can call me cruel or a murderer if I do not promise, deceive, call to, or accept him. Until now heaven has not ordained that I love, and to think that I shall love of my own accord is to think the impossible.

Let this general discouragement serve for each of those who solicit me or his own advantage; let it be understood from this day forth that if anyone dies because of me, he does not die of jealousy or misfortune, because she who loves no one cannot make anyone jealous, and discouragement should not be taken for disdain. Let him who calls me savage basilisk avoid me as he would something harmful and evil; let him who calls me ungrateful, not serve me, unapproachable, not approach me, cruel, not follow me; let him not seek out, serve, approach, or follow in any way this savage, ungrateful, cruel, unapproachable basilisk. For if his impatience and rash desire killed Grisóstomo, why should my virtuous behavior and reserve be blamed? If I preserve my purity in the company of trees, why should a man want me to lose it if he wants me to keep it in the company of men? As you know, I have wealth of my own and do not desire anyone else’s; I am free and do not care to submit to another; I do not love or despise anyone. I do not deceive this one or solicit that one; I do not mock one or amuse myself with another. The honest conversation of the shepherdesses from these hamlets, and tending to my goats, are my entertainment. The limits of my desires are these mountains, and if they go beyond here, it is to contemplate the beauty of heaven and the steps whereby the soul travels to its first home.

And having said this, and not waiting to hear any response, she turned her back and entered the densest part of a nearby forest, leaving all those present filled with admiration as much for her intelligence as for her beauty.

Another interesting theme in the book is that of jealousy. There is an episode on this topic that is my favorite in Don Quixote. An episode that even Kadare found compelling, as he made it a central theme in his novel The Accident. An episode that I will present here in all its genius, along with Kadare's parallel and interpretation.

[To be continued...]